Holly has a site for things

Personal website for Holly Richko- software engineer, podcaster, dovahkiin.

Formatting Noisy Data For Machine Learning

by xoxo Holla

Formatting Noisy Data for Machine Learning

Overview

A key factor in the success of any machine learning(ML) project includes formatting your data so that the algorithm you choose has “good” data to work with. What do I mean?

- The data is accurate,

- Features that are quantitative are scaled (if needed),

- Features that are qualitative are classified.

For my current project, I’m trying to identify the selling price of recipes you can create in the Nintendo game Zelda: Breath of the Wild. Unfortunately there isn’t a publicly available database of all ingredients and possible recipes, so I did some googling to see what online resources had data that could be scraped the most easily.

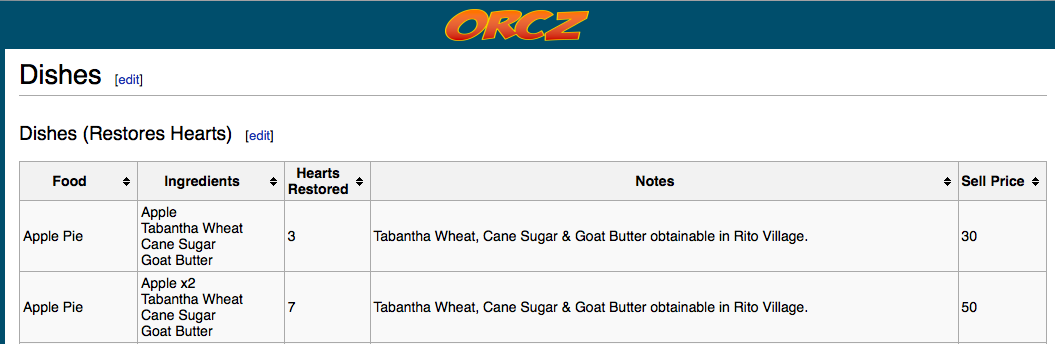

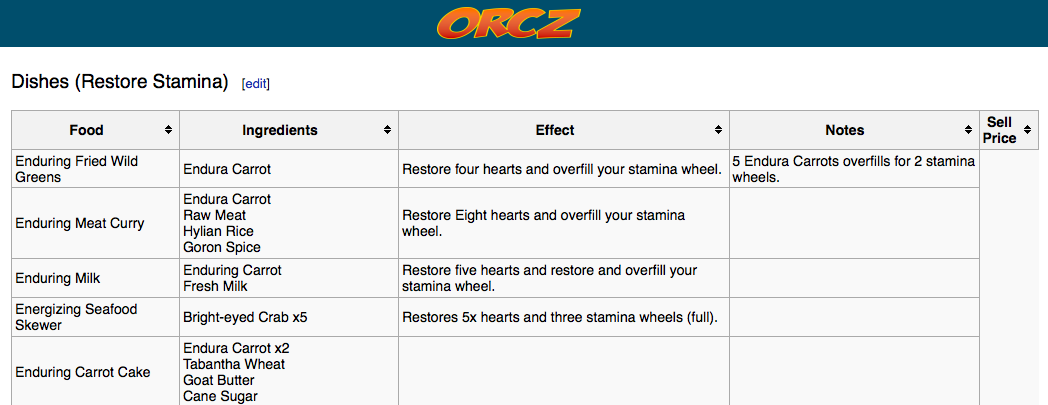

My source information does have several tables of recipes to use! That said, not all tables have the same fields or columns, and some values for these columns contain information that not easy for a program to read without some help:

Example 1- this table looks like it’d be easy to convert

Example 2- this table has information that is contextual and may need some work

To achieve this, we can use some old school command line tricks, a little script work, as well as one hot encoding and scaling techniques so that my training and test data is in a format that’s easier for my ML project to read.

Command line tips

csvkit

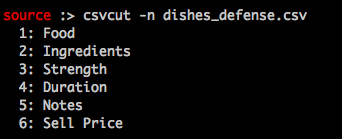

csvkit is a set of command line tools (written in python!) that help you work with CSVs. Since I use this set of tools at work regularly, I felt comfortable using csvcut to extract specific columns from my source data. Once I had all the tables of possible dishes from my internet resource source saved to CSV files, I used the command:

$ csvcut -n FILE

To quickly examine columns and see how much work would be needed to condense all files into one large resource.

Example output

Then, once I had established a list of columns I would need to add or remove from each source table, I could use csvcut again to select either a specific column(s) or extract all but a few column(s) as my output:

$ csvcut -c 5 dishes_defense.csv > just_notes.csv

// this gives me just the notes column from the CSV

$ csvcut -C 5 dishes_defense.csv > trimmed_defense.csv

// this gives me all columns except the notes column

Once I had all the columns/fields in my source CSV files in the same order, I could use the tail command to dump all contents of my CSVs starting at a specific row (like row 2, so that I’m not copying headers) into a condensed file:

$ tail -n +2 dishes_defense.csv > all_dishes.csv

Now I have one large file of data! That said, there’s still some work that I need to do so that my data is in a format a ML algorithm can read and use.

Scripting for specific use cases

So, I now have one CSV file containing all source data, but there’s some features that I’d like to add using some of this information:

- Looking over the names of recipes, the first word in a recipe’s name could indicate its value or not:

Recipe Name

Chilly Simmered Fruit

Mighty Crab Risotto

Mighty Porgy Meunière

- The source data also indicates whether an ingredient can be used in a recipe more than once (For reference, you can submit up to five ingredients to create a recipe in Zelda: Breath of the Wild). It’s currently in a format that’s great for humans, but not so great for a machine:

Recipe Name, Ingredients

Mighty Herb Sautè,"Mighty Porgy x2,Mighty Thistle,Bird Egg,Goron Spice"

Mighty Porgy Meunière,"Tabantha Wheat,Goat Butter,Mighty Porgy x3"

//ingredients are a string and some ingredients have x3 indicating multiples

I could use the pandas library to hot encode some of this information (more on this further down in my post), but it might be more practical to just write a script that does this for me.

Using csv

Python’s CSV library has some great features that make it easy to work with complex data structures. For example, using DictReader and DictWriter you can treat CSV rows as if they are dictionaries, making it more legible to extract data from specific columns (provided your source data and an output file have headers):

with open('raw_data.csv',) as csvfile:

reader = csv.DictReader(csvfile)

for row in reader:

# do all the things!

This proved especially useful writing my formatted data to an output csv. Assuming I had a dictionary of recipes from my input file I could iteratively work through each recipe and its values, creating a formatted_row dictionary that could be written to my output CSV using DictWriter.

for recipe in recipes:

# work through the values for all columns, performing additional formatting as needed

formatted_row['Sell Price'] = recipe['Sell Price']

# write this information to a dictionary I can then reference efficiently when creating my output CSV

write_to_output[recipe['Recipe Name']] = formatted_row

with open('output.csv', 'w') as csvfile:

writer = csv.DictWriter(csvfile, fieldnames=HEADERS)

writer.writeheader()

for formatted_recipe in write_to_output:

writer.writerow(formatted_row)

Extracting Recipe Names

I can write a simple method to split a recipe’s name on any whitespace character, which will give me a list of separated words. I only want the first word in my recipe name to work with so I can whittle down my method even more:

def get_recipe_effect(recipe_name):

return recipe_name.split(' ')[0]

Once I have this, I can take the first word in this list and add it to a dictionary of all possible first words in recipe names to be used later when I write my data to an output CSV:

recipe_effects = {} # my dictionary that I'll use later when I hot encode

name_effect = get_recipe_effect(name)

if 'name_' + name_effect in recipe_effects: # `name_` prefix for output readability

recipe_effects['name_' + name_effect] += 1

else:

recipe_effects['name_' + name_effect] = 1

Once I’ve done this for every recipe in my input file, I can write some conditional logic that hot encodes the first word of each recipe’s name so that my output has a column for every possible first word and whether it applies to that recipe (0 indicating no, 1 indicating yes):

for key in recipe_effects:

if recipe['Recipe First Word'] in key: # if the first word of the recipe I'm about to write add to my output file is the same as my key

formatted_row[recipe['Recipe First Word']] = 1

else:

formatted_row[recipe['Recipe First Word']] = 0

Counting Ingredients

Similar to recipe names, I can write a method that splits each string of possible ingredients into a list, and then applies some if/else logic to check if each entry in my ingredients list contains x and a number, indicating multiple ingredients.

def ingredients_prep(ingredients_list):

row_ingredients = {}

split_up = ingredients_list.split(',')

for item in split_up:

if " x" in item:

working = item.split(' x')

ingredient_key = working[0]

multiplier = int(working[-1].strip()[-1])

row_ingredients['ing_' + ingredient_key] = multiplier

else:

row_ingredients['ing_' + item] = 1

return row_ingredients

I’ll then add a column for every possible ingredient to my output CSV and update each recipe’s row with the number of each ingredient supplied (marking 0 if that ingredient was not used)

all_ingredients = {}

prepped_ingredients = ingredients_prep(row['Ingredients'])

for key in prepped_ingredients:

if key not in all_ingredients:

all_ingredients[key] = 1

else:

all_ingredients[key] += 1

# later, writing to my output CSV

# recipe['Ingredients'] is a dictionary of ingredients in a single recipe,

# and the count of those ingredients used

for key in all_ingredients:

if key in recipe['Ingredients']:

formatted_row[key] = recipe['Ingredients'][key]

else:

formatted_row[key] = 0

This may take more lines of code to achieve than with some intricate pandas knowledge, but my work is legible and I can quickly check and see if there are any outliers that don’t match expected values for my columns.

Now that I have an output CSV with some more uniform formatting, I’m ready to import this data to a DataFrame using pandas.

One Hot Encoding

First, what is one hot encoding? Rakshith Vasudev has a great explainer on this process where he states:

One hot encoding is a process by which categorical variables are converted into a form that could be provided to ML algorithms to do a better job in prediction.

Essentially, if you have one column where the values are categorical- like

color

'blue'

'red'

'green'

One hot encoding will translate this information so a ML algorithm can interpret it more easily. With my previous example, your result would be after on hot encoding:

color_blue, color_red, color_green

1,0,0

0,1,0

0,0,1

I had mentioned earlier that I could use pandas to hot encode some classifying information. When I was first working on formatting my data, I had explored using the getdummies method to achieve this, but then on inspecting those results I realized I would have a bunch of columns that look the same except for the number of ingredients in the feature name:

import pandas

def separate_ingredients(list):

for ingredient_list in ingredients:

if type(ingredient_list) == str:

separated_ingredients.extend(_prep_columns(ingredient_list))

return separated_ingredients

def _prep_columns(list):

columns = list.split(',')

return columns

test = pandas.read_csv('raw_data.csv', delimiter=',')

hot_ingredients = pandas.get_dummies(test['Ingredients'], prefix='ing')

print(hot_ingredients.columns)

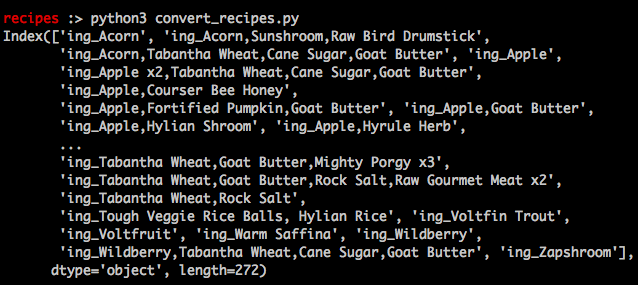

results

I noticed that my resulting columns would need to be split up another level because my ingredients were currently one large string of comma separated ingredients. Additionally, ingredients that be used in a recipe multiple times were designated in the source data with a x and the number of times they could be used. To really classify this information, I would need to create a script to separate the ingredients and handle the x scenario in the source information.

That said, for future projects I can see this being a handy method to quickly hot encode your data!

Scaling

Once I had my finished output CSV, there were a few more columns that had data could be mis-interpreted by my ML algorithm if I left as-is. Instead, I scaled the data in these columns so that all data was on a scale of 0.00 to 1.00:

import pandas

test_df = pandas.read_csv('output.csv', delimiter=',')

to_scale_df = test_df[['Duration', 'Sell Price', 'Health Effect Details']]

to_scale_df -= to_scale_df.min()

to_scale_df /= to_scale_df.max()

# drop my original columns add my newly scaled columns to my DataFrame FINAL

test_df = test_df.drop(['Duration', 'Sell Price', 'Health Effect Details'], axis=1)

FINAL = pandas.concat([test_df, to_scale_df], axis=1)

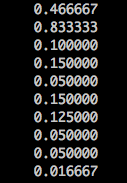

My scaled columns would look something like:

And that’s it! OR IS IT? I can separate this data into a training and testing set. There’s also some functionality in pandas that I could use to put together my source data so I don’t have to lean on bash commands. I could also refactor some of my if/else logic so that I’m completing it in one line. That said, condensing those statements into one line can make my code less readable to someone else (or me two weeks from now!).